The Science Skill Too Many Classrooms Ignore

The Writing-Science Connection

We say we want better science students—critical thinkers who can analyze evidence, explain ideas clearly, and engage in scientific reasoning. But we often ignore one of the most powerful tools for building those skills in the elementary years: writing. Decades of research in science education has shown that engaging students in writing can significantly improve their analytical thinking and problem-solving skills. Yet in many schools, especially at the elementary level, dedicated “science time” is minimal compared to reading or math. If we want young learners to truly think like scientists, we need to have them write like scientists.

Writing isn’t just a “literacy skill.” It’s a science skill. Especially at the time where students are beginning to think of themselves as learners, writers, scientists. The messy, rigorous thinking at the heart of science isn’t multiple choice – it’s constructed, explained, and argued. And that means it’s written.

Writing Helps Students Process and Retain Scientific Concepts

Let’s start with something well-supported by research: students who write about what they learn in science retain more information and understand it more deeply. Educational studies consistently find that when students write in response to science content, they deepen their understanding and are more likely to remember the material over the long term. This is because writing forces students to do something active with information: to organize it, articulate it in their own words, and make connections. By transforming rudimentary ideas into coherent knowledge on the page, students are engaging in exactly the kind of cognitive processing that cements learning.

Consider two students learning about photosynthesis. One reads the textbook and answers a few end-of-chapter questions. The other writes a short paragraph explaining, in their own words, how sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide turn into glucose in a plant. Which one has to think harder? Which one is more likely to remember the concept a week later? Research would bet on the writer. Writing about scientific ideas prompts students to clarify what they know and fill in gaps, leading to stronger schema (mental frameworks) for the topic – not just isolated fact recall.

This benefit isn’t limited to older students; it holds true for elementary children as well. Even young learners in K–5 who regularly write about science topics show improved content retention and understanding. In one study, 5th graders who wrote explanations of science phenomena showed better grasp of cause-and-effect relationships than those who only studied the facts. The act of writing helps students of all ages “learn by doing” with content, which means they process it more deeply. They’re not just memorizing that plants need sunlight – they’re explaining why, which helps the knowledge stick.

Structured Writing Builds Scientific Reasoning

Science is fundamentally about structure: hypotheses lead to experiments, which lead to results, which lead to explanations. Good writing mirrors this. Yet too often, we ask students to “write in science” without giving them the organizational structures to succeed. A jumble of disconnected facts on a page is no better than a jumble of thoughts in a student’s mind. Research on writing instruction shows that teaching common text structures (such as cause–effect, problem–solution, or compare–contrast) can greatly improve students’ ability to organize and communicate ideas. In fact, awareness of these text structures improves both reading and writing outcomes for students across elementary, middle, and high school. By learning to structure an explanation or argument logically, students are also learning to structure their thinking.

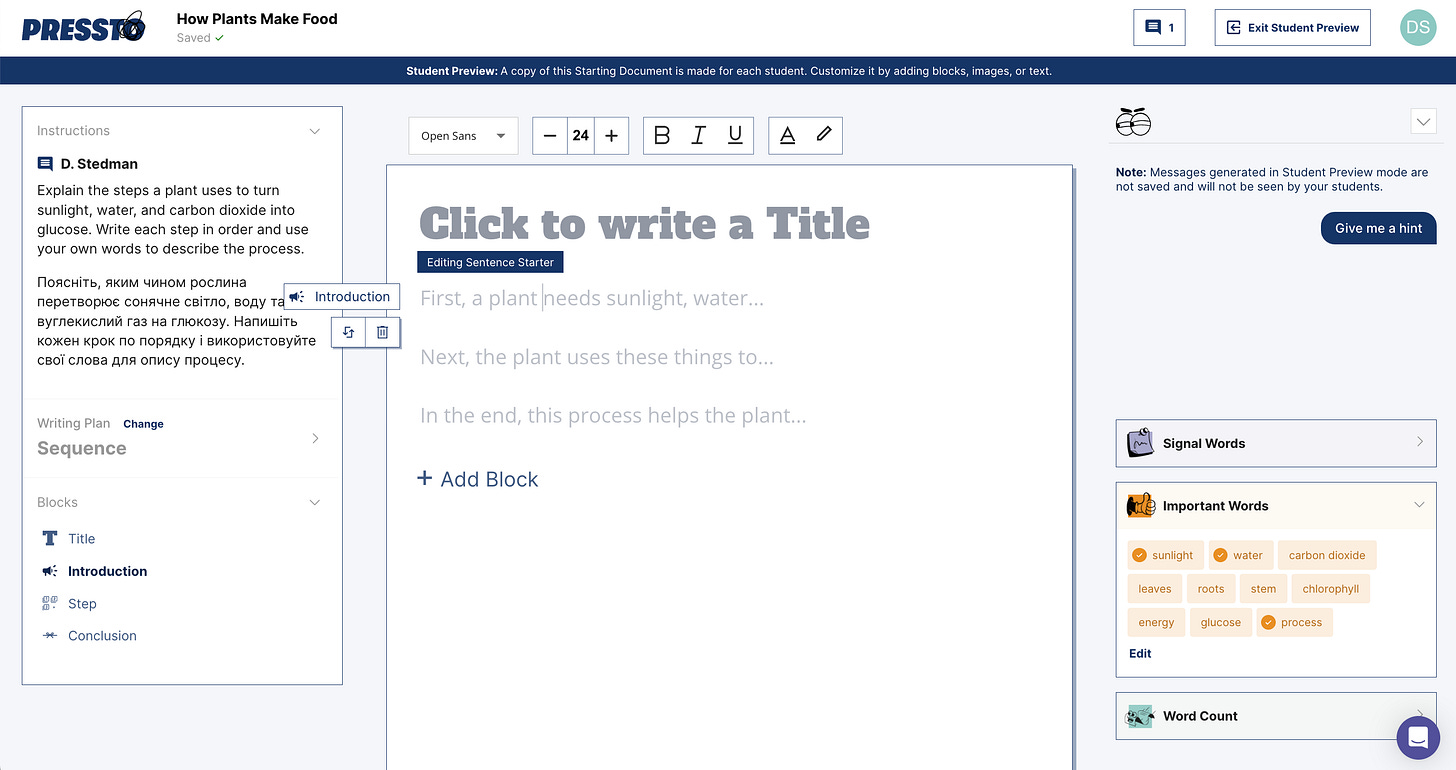

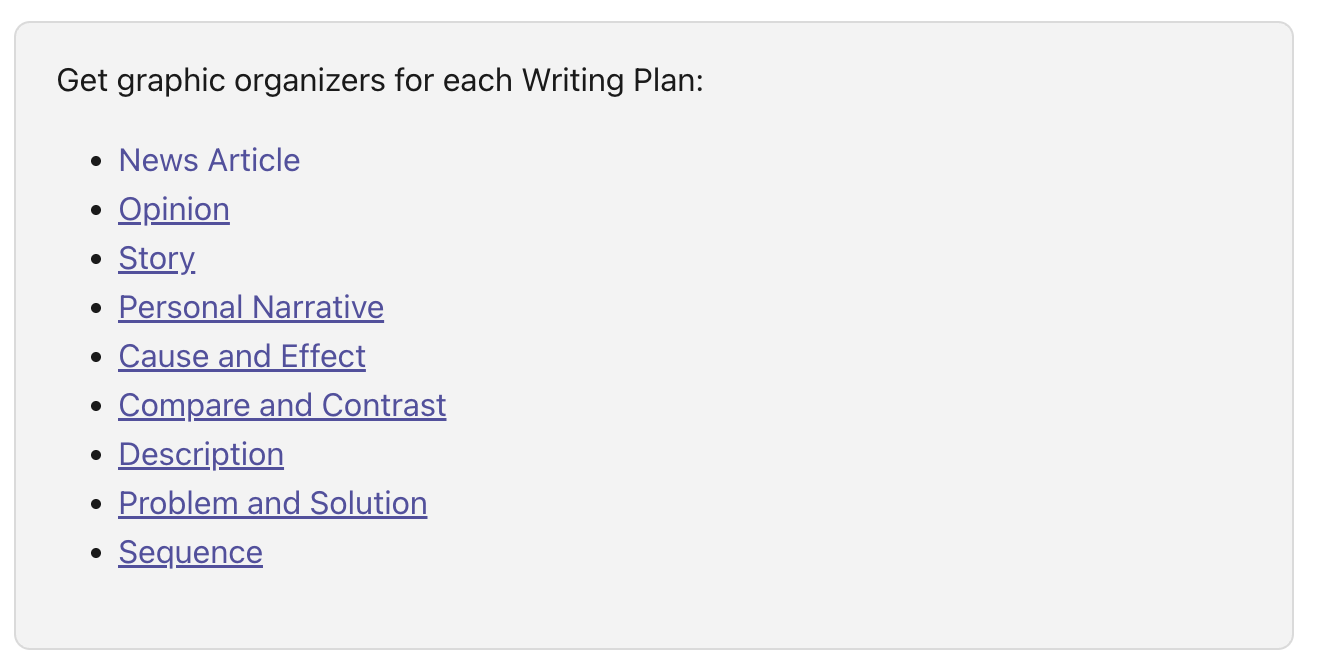

Pressto’s approach is rooted in helping students choose from common text structures so their science writing has a clear shape. This isn’t just about writing better – it’s about thinking better. When students have a scaffold (like a template or graphic organizer), they learn to evaluate evidence, sequence their thoughts, and draw connections – exactly the cognitive moves scientists make when building an argument or explanation.

Want an example? Imagine a middle school assignment on climate change. Students could be given a structured task like this:

Prompt: Compare two strategies for reducing carbon emissions.

Writing Plan: Compare and Contrast

Writing Blocks: Introduction, Similarity, Difference, Image with Caption, Conclusion

With this scaffold, a student isn’t left floundering on how to organize their essay – the roadmap is laid out. This structured approach guides them to engage in scientific reasoning: they must consider multiple solutions, weigh evidence for each, and synthesize their findings. The thinking is built into the writing plan.

This kind of structured writing can start early. Even at the elementary level, teachers can use simple frameworks to help children articulate science concepts. For instance, a 2nd-grade class might compare the life cycles of a butterfly and a frog using a similar compare/contrast plan. The key is providing a clear scaffold so that students focus on developing ideas and reasoning, rather than struggling with how to organize their thoughts. In one classroom, teachers had third-graders identify the components of a strong paragraph from a model text, to internalize the framework they would later use in their own science writing. Such supports have been shown to drastically improve the quality of students’ explanations and arguments, because the structure helps channel their scientific thinking in a logical way. It’s like giving them the skeleton of a scientific argument, which they then flesh out with their own observations and evidence.

There’s evidence that this approach pays off in better reasoning skills. In a study with biology students, those who wrote using structured prompts showed significantly greater gains in analysis and inference skills than peers who only did traditional Q&A or quizzes. In other words, learning to organize and explain their science knowledge made them better scientific thinkers. When we teach students how to structure an explanation (say, by making a claim, backing it with evidence, and providing reasoning), we are really teaching them the architecture of scientific reasoning.

Writing Is an Authentic Scientific Practice

In real science, writing isn’t optional—scientists draft lab reports, publish papers, and argue from evidence. The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) recognize this by naming “Constructing Explanations” and “Engaging in Argument from Evidence” as core practices. By middle school, students are explicitly expected to write arguments supported by data to explain phenomena or advocate solutions. Being a scientist is as much about communicating ideas as it is about generating them.

Yet classrooms too often treat writing as an ELA responsibility, not a science one. Students may read about the water cycle in science, then write a poem about it in language arts. That’s not integration—it’s avoidance. If scientists spend much of their day writing, students should be doing age-appropriate versions of the same: recording observations, formulating explanations, and arguing from data.

This doesn’t require essays. A few sentences explaining “Why did the temperature in our beaker rise?” or “What might happen if we used a different solvent?” is enough to push students to reason like scientists. Regular micro-writing tasks—quick reflections, exit tickets, short explanations—build habits of scientific reasoning and make science something students explain and discuss, not just memorize. Research shows that combining discussion with writing produces the strongest learning gains: talk clarifies ideas, while writing consolidates them into lasting understanding.

The challenge, of course, is time. Frequent short writing assignments can feel overwhelming to grade. This is where tools—including AI—can help by providing timely, supportive feedback without replacing the student’s own thinking.

AI Writing Tools Can Support – Not Replace – Science Thinking

In the age of generative AI, it’s true that a student can ask ChatGPT to “Explain how photosynthesis works” or even “Write my lab conclusion.” Does this mean writing is obsolete in science education? Absolutely not. What it means is we need to rethink how we teach writing in science. If writing is treated merely as a final product to be graded, then yes, students might be tempted to outsource it. But if writing is embedded as a thinking process, we can still ask students to “show their work” – something AI can’t easily do for them.

The key is to use AI as a writing buddy, not a ghostwriter. For instance, Pressto’s Writing Blocks™ system encourages students to draft each part of an explanation in structured chunks (introduction, evidence, reasoning, conclusion). Along the way, an AI Writing Buddy might pop up with a nudge: “Have you explained why this result matters?” or “Do you have data to back that claim?” – without outright giving the answer. This kind of real-time feedback can be incredibly helpful. Research on effective writing instruction emphasizes timely, facilitative feedback during the writing process, not just after a final draft. In practice, however, teachers often lack time to give detailed feedback on every student’s draft in progress. An AI assistant can help fill that gap by providing instant suggestions or reminders, so students can revise and strengthen their explanations as they write.

It’s important to underscore that AI should support the student’s thinking, not do it for them. The value of writing lies in the cognitive effort – deciding what’s important, how to phrase it, how to link evidence to a claim. If a machine does all that, the student learns very little. As writing expert Dr. Steve Graham puts it, if AI handled all the data and wrote your science paper, “what do I actually know?” [Collaborative Classroom]. Reading an AI-generated answer might tell a student the result, but it bypasses the mental work that leads to true understanding. We don’t want that. Instead, the vision is like the shift that happened in math education after calculators became common: we moved away from rote calculation toward requiring students to explain how they solved the problem. In writing, AI can handle low-level mechanics or offer ideas, but students can be asked to focus on the high-level reasoning and personal insight. For example, an AI tool might suggest alternative wordings for a hypothesis or point out if a student’s conclusion lacks a clear explanation of why the data matters. The student then uses those hints to improve their work. They’re still “showing their thinking,” just with a helpful coach on the side.

Pressto’s model of a Writing Buddy™ is a case in point: it’s designed to “write with them, not for them,” guiding students using research-backed feedback principles. The AI might remind a student to include relevant vocabulary or to check that their conclusion addresses the hypothesis. It won’t generate the conclusion from scratch – that remains the student’s job. By doing this, we ensure that writing in science class remains a thinking exercise, even with AI in the mix. The student is still actively constructing knowledge; the AI is an assistant, like a lab partner who says “Hey, did you consider this piece of data?”.

This approach aligns with how educators are beginning to handle AI in the classroom: as an opportunity to emphasize process. We can let students use tools to brainstorm or to catch grammar mistakes – things that don’t replace the need to understand the science. In fact, learning to use AI effectively could become another valuable skill (imagine students asking a science AI, “Am I missing any factors in my explanation?” and then critically evaluating the AI’s suggestions). The bottom line: writing is not obsolete. If anything, the rise of AI makes it more important that we double down on teaching writing as a way of learning, not just assessing. We need to explicitly tell students: we care about how you arrived at that explanation, not just the final answer. AI can help get to a polished product, but the scientific reasoning – the part we really want to develop – has to come from the student.

Writing Needs to Be Embedded in Science Classrooms

This isn’t about piling on long essays. It’s about embedding purposeful, bite-sized writing into science instruction—just as we embed hands-on experiments, discussions, and observations. Writing in science can take many forms beyond the formal lab report, and it can be woven into daily lessons without derailing content coverage.

Consider a few examples:

Animal Habitats: After a lesson on desert ecosystems, students write a few sentences comparing how frogs and lizards survive. (Text structure: compare/contrast – focusing on water needs or skin texture.) This cements a science content goal while giving practice with explanatory writing. Research shows that using science as the context for literacy practice in early grades boosts motivation and improves both science and literacy outcomes.

Life Cycles: When studying butterflies, students write a short sequence explanation of the metamorphosis process. They practice transitional words like first, next, then, while also reasoning about cause and effect (e.g., because the caterpillar outgrew its skin, it formed a chrysalis). Writing out the sequence helps them understand the process, not just memorize stages.

Weather and Water: During a reading block, after listening to a nonfiction book about clouds, students can write a short explanation of how clouds form. They meet literacy objectives (comprehension, writing structure) while reinforcing science concepts—an efficient and meaningful use of time.

Notice that none of these examples require more than a paragraph or two. The goal is frequent, authentic writing woven into science, not occasional “assignments” that feel separate from learning. In these grades especially, students need lots of varied opportunities to write as part of learning content. When writing is taught in tandem with science, each supports the other: writing strengthens comprehension, and reading scientific texts provides models for writing. It’s a virtuous cycle.

From a practical standpoint, this integration also helps solve the time crunch. As Science and Children put it, instead of asking, “How can I fit writing into my science time?”, teachers might ask, “How can I use science during my writing time?” By blending the two, students practice essential literacy skills while deepening their scientific understanding.

Conclusion: If You Want Stronger Science Students, Teach Writing

The science classroom shouldn’t be a place where writing goes to die. It should be where writing comes to life – as a tool for thinking, learning, and making sense of the world. Writing instruction, done well, doesn’t distract from science at all. It is science. When students write, they are actively doing what scientists do: asking questions, gathering and analyzing information, drawing conclusions, and communicating them.

In fact, far from detracting from other subjects, increasing focus on writing can boost performance across the board. Empirical evidence shows that teaching writing makes students better readers (and teaching reading makes them better writers). That’s because so many cognitive skills overlap – organizing ideas, understanding text structure, synthesizing information. By learning to write like scientists, students also sharpen their ability to read scientific texts critically and to articulate their thoughts clearly in any subject.

With modern tools like Pressto, integrating writing into science has never been more feasible. Teachers can now give frequent, low-stakes writing assignments (e.g. quick reflections, explanations, or CER – Claim/Evidence/Reasoning – statements) without drowning in paperwork, thanks to real-time feedback and scaffolded prompts. This means we no longer have to choose between “covering content” and “teaching writing.” We can do both, simultaneously, and more effectively. It’s exactly the kind of innovation that educational leaders have been calling for – bridging the gap between knowing what works (writing-to-learn strategies) and actually making it happen in the classroom.

If we want students who can analyze data, reason from evidence, and communicate clearly, we don’t need to double the science curriculum or cram in more multiple-choice drills. We need to give students the opportunity and guidance to write as a way of learning science. From the earliest grades through high school, writing can be the thread that connects and reinforces every science lesson. As one teacher told her second graders: “A good scientist is also a good writer” [NSTA]. Embracing that mantra could be transformational. Let’s teach our students to write like scientists – our future inventors, doctors, engineers, and researchers will thank us for it.

Sources:

National Commission on Writing, The Neglected “R”, 2003.

Quitadamo, I. & Kurtz, M. (2007). Learning to Improve: Using Writing to Increase Critical Thinking Performance in General Education Biology.

Pressto (2023). Writing in the Age of AI: Embracing AI and Effective Pedagogy to Revolutionize Learning, Jeanne R. Paratore.

Rivard, L.P. & Straw, S.B. (2000). The effect of talk and writing on learning science. Science Education, 84(5), 566–593.

Savvas Learning (2023). Why Writing Development and Instruction Matter.

Education Week (Jan 2023). How Does Writing Fit Into the "Science of Reading"?, Stephen Sawchuk.

Graham, S. (2023). Keynote on Writing Instruction and AI. Collaborative Classroom Blog.

NSTA (Nov 2020). Science in the Literacy Block, Lott & Clark – Science and Children Journal.

NSTA Blog (2015). Student Writing in Science, Mary Bigelow.

Next Generation Science Standards – Appendix F: Science and Engineering Practices.